|

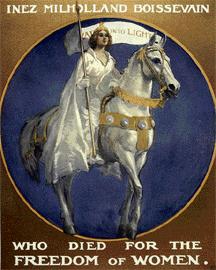

Jane Barker of the Turning Point Suffrage Memorial

and the restored portrait of Inez Milholland Boissevain,

Sewall-Belmont House, 2011. Photo © by JT Marlin. |

New York, March 8, 2016–This day, March 8, is the 105th Women's Day, later called "International Women's Day".

It was little noted in New York City five years ago on its centennial, despite the day having been born and reborn here.

I posted something about it on Huffington Post.

In 1908 on this day, 15,000 women marched down Fifth Avenue in support of working women. Many of their goals were advanced by the largely successful 13-week shirtwaist workers' strike of 1909.

Inez Milholland was deeply involved in assisting strikers as a first-year law student at NYU.

The owners of one factory never settled their strike–the Triangle factory, where the tragic fire of March 25, 1911 occurred. The fire did not result in punishment of the criminally negligent factory owners, but it provided the emotional inspiration for:

- The suffrage parade in New York City in 1912,

- The Washington parade in 1913.

- The picketing of the White House in 1917, which led directly to woman suffrage in 1920.

Inez Milholland had a part in all three of these events, which turned around public opinion on the issue of woman suffrage. She led on horseback the parades in 1912 and 1913, and her death in 1916 was the inspiration for the confrontation between the National Woman's Party and President Wilson that in turn instigated the White House picketing and the imprisonment of picketers.

Today, despite the 95-year-old victory of the suffragists and the fact that young women are now better educated than men, working women are still trailing men in pay.

New York Origins of Women's Day

Descriptions of a Women's Day go back to March 8, 1857, when needle workers in New York City reportedly demonstrated for higher wages, a reduction in the workday from 12 to 10 hours, and no uncompensated work. Their protest was reportedly dispersed by shots from an army unit and by the arrest of 70 workers.

Two key woman suffrage leaders of the second half of the 19th century–Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony–failed to obtain votes for women and died disappointed in 1902 and 1906. Their leadership torches were picked up by a new generation of brave women leaders who succeeded in their goal. One of them was Inez Milholland.

The year Susan B. died, the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union was founded. Needle workers in New York protested on March 8, 1908 under the auspices of Branch No. 3 of the New York City Social Democratic Women's Society. Women marched down Manhattan for better pay and a shorter workday–and in addition they called for woman suffrage and better protection against child labor.

In 1908 and 1909, the needle workers benefited from the support of wealthy women like Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Anne Morgan, and also from a large contingent of volunteers from women's colleges like Bryn Mawr and Vassar. Inez Milholland was one of the most visible of these women in 1908, when she was a junior at Vassar College.

She signed up two-thirds of Vassar students in a suffrage organization. She was forbidden to hold a suffrage meeting on the Vassar campus, so she scheduled it across the road at Poughkeepsie's Calvary cemetery in June 1908. Vassar's President Monroe Taylor had threatened to expel anyone who attended, but faculty and alumnae showed up along with 40 students and he thought better of expulsion.

During the 13-week shirtwaist-worker strike of 1909, Inez Milholland was a law student at NYU, located next door to the Triangle Shirtwaist factory on Washington Square East. She picketed with the workers and explained to them their rights.

Milholland became an icon of the suffragists in 1912 and 1913 when she rode horseback in costume at the head of the New York and Washington suffrage parades.

In 1913, when she surprised her friends and got married in secret, she was called "the fairest of the Amazons" by the

NY Times.

In 1916 she campaigned against Woodrow Wilson for not supporting the Anthony Amendment to give women the right to vote, and she collapsed during the strenuous effort, dying (it was recorded) from "pernicious anemia", exhaustion and what we would call today counter-productive medical care while she was traveling (her prescriptions included arsenic and strychnine). Her death precipitated White House picketing and President Wilson's capitulation.

Woman Suffrage and Equality

The suffrage amendment was finally ratified in 1920, 80 years after it became a gleam in Stanton's eye and 50 years after the right to vote vote was recognized for all men.

So now it's nearly 95 years after the first election in which all U.S. women had the right to vote. Has the right to vote spelled equality for women? In the educational area, increasingly so. In a word, young women are now better educated than young men. As I said five years ago in my

Huffington Post article:

Women receive 58 percent of the bachelor degrees and 61 percent of the master's degrees in the United States. Of women 16 years and older, 37 percent work in management, professional and related occupations, more than men (for whom the figure is 31 percent). But women in the United States still earn just 77 cents for every $1 earned by men. Of the 259 members of the Financial Women's Association just surveyed in New York City, 96 percent say they get paid less than men for comparable work. In 2008, 86 women served in the 110th U.S. Congress, just 16 percent of the 535 seats. The proportion of women in state legislatures is slightly higher, 24 percent.

The U.N. supports and promotes International Women's Day, which is outstanding. But do its own actions match its words? When I wrote in 2011, it was promoting women at a slower rate than men:

In 2006 and 2007, the number of women appointed as directors (D-1 and D-2s), assistant-secretaries-general (ASG) and under-secretaries general (USG) was 25 percent. It was 38 percent in the professional categories.

The worst news is how poorly women fare in developing countries dominated by non-Western culture. Women's choices are severely limited and in some countries women have few human rights. International Women's Day therefore is needed not just to celebrate the achievements of suffragists but to extend the rights of women where they are not respected–in the United States and globally.

© 2016 JT Marlin.

Follow me on twitter: @cityeconomist.